An in depth look into caching (Part 1)

The world-wide web

Nobody calls it that way anymore. But the term is oddly descriptive. Nowadays, it’s all about interconnected systems. You log into your mobile game with your Google account, or maybe your Facebook account. You search for some page (of which you never ever knew its address - honestly, who types URLs anymore?) and expect the whole process of typing your query, finding your page, and going into that, to be faster than bookmarking it. You find it in half a second, it was a news page, and hit the button to share on Twitter.

Increasingly, the difference between offline and online is slowly fading, and the separation between services even more so.

At the heart of it all, there is a huge, world-wide web of server-to-server communication protocols. Usually REST, but not necessarily always so. And for it to work as described above, it all has to be fast. It has to respond, as they say, in real-time - because everything above 50 milliseconds is fake-time.

And this includes ads, which is where we at Jampp come in.

Enter Real-Time systems

So, we’ve got a web (or part of it) that’s powered by a set of services working together, communicating in real-time. But what does real-time really mean? It usually means there’s a user behind that process waiting for its answer, and it expects the answer to pop up in a reasonable time. It’s not always measured in milliseconds, sometimes a few seconds is fine, but it’s certainly not minutes. For ads, for instance, it’s around 100ms. That’s milliseconds.

But the systems are complex - or they wouldn’t be useful. And they get more complex every day. So, aside from Moore’s law, how do you cope with increasing complexity, with stricter and stricter timing requirements?

We’re looking for an architecture that can:

- Handle lots of requests per second. Like 200K rps.

- Handle each request in milliseconds. 100ms to be precise.

- Handle increasing complexity.

And yes, we’re talking architecture, not technologies. While architectures are empowered by technology, it’s usually the architecture itself the one defining how and whether an app can scale with real-time constraints.

Let us look at an example.

Example: The smart banking system

Typical example. It gets requests for deposits or withdrawals, and it updates an account. Simple. Nothing complex. It can scale nicely with a number of techniques, like sharding, two-phase commits (when transactions need to span shards), etc.

Hardware that is fast enough, can make the system meet the 100ms deadline even under big loads when using sharding. Banks have this very well tuned.

Let’s spice it up a bit. Now, to give an example, the system wants to reply to every transaction with both the current balance, and a projection of future balances, as an estimate of how the user is spending (or earning) her money.

The system suddenly needs access to a lot of historic transaction data, do a lot of math, and things quickly get out of hand.

It’s essential, to be able to guarantee real-time performance, that requests imply very little work. It will never be viable to perform heaps of computations on each request and still manage to meet a millisecond deadline, so the trick lies in simplifying the problem to the point when requests become simple, yet produce acceptable results.

There are several ways to get this back to manageable:

-

Precompute: have the projections precomputed by the time the request comes in. Update after transactions change the balance. After answering, but before the next request.

-

Throw a lot of computing power (and money) to the problem. The fact that this still is constrained to the history of a single user makes it at least scalable (it might not always be the case).

-

Do approximations. Keep a truncated transaction history handy to do the projection quickly, or use algorithms that allow online update of the projection, even if it’s approximate.

So, on the one side, we have technological solutions, in the form of technologies or very fast hardware that happens to be fit for solving the problem at hand, or at least help. And on the other, we have architectural solutions, that involve introducing tradeoffs to shape the problem back into a workable state.

Technological solutions tend to be expensive, but it’s not always the case. There are very nice examples of technologies that are efficient, both in time, space, and money, for some kinds of problems. Knowing them is of course extremely important, so the first step in any kind of work involving real-time at scale, is due research. Figure out the options, test them even.

Most of the time, though, fast systems are expensive, and/or inflexible. After all, they are usually architectures made reusable by packaging them into a product, and come with their own set of tradeoffs. Take NoSQL, for instance. It takes away ACID ity (mostly consistency) and querying capabilities, trading it for speed and ease of scalability. They might be useful, but they won’t work in all cases, and the tradeoffs need to be considered carefully before adoption.

Most of the time, we can get a better fit by designing our own architecture with our own, better-fitting tradeoffs. Though it takes effort and experience, and a lot of thinking.

Here at Jampp we have this habit of thinking from time to time, it saves us from having to throw money at some problems that have cheaper solutions, so we’re going to try and share some of our experience in this post (and others), and maybe it will take you a bit less effort and a bit less experimentation to get to your own efficient solutions.

We’ll start with simple caching tricks, another way to get the latency down.

Caching - The Neat Trick

Yeah, caching TNT. Because it’s like TNT you sprinkle on your systems to make roadblocks go away.

But like TNT, it requires careful handling. Someone said it of regexes, and we can say it of caching too. If you add caching to solve a problem, you get two problems. But caching done right can actually solve problems, just like regexes can solve you some too. The trick lies in understanding its limitations. And its pointy edges.

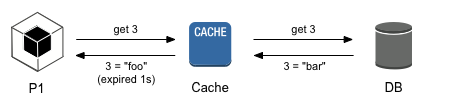

Caching can be divided in two quite different approaches. One we’ll call pessimistic caching, and the other optimistic caching. Most know pessimist caching, it’s like Varnish, and so many CDNs out there. When you get a request, you remember the reply, and decide to give that same reply to similar requests for a while.

There are tons of subtleties in deciding which requests are similar, for how long to cache, and quite importantly, how to limit the amount of storage needed to store memorized replies.

In general, in code, pessimistic caching looks like this:

def get_user(user_id):

cached_user = user_cache.get(user_id)

if cached_user is None:

cached_user = user_cache[user_id] = database.get(user_id)

return cached_userYes, that’s Python. So you will probably want to write it more like:

@cached(user_cache)

def get_user(user_id):

return database.get(user_id)But pessimistic caching can only improve your average response time, but not your worst. When you get a request for which you haven’t got a fresh answer memorized yet, you still have to compute it, and spend lots of time computing it, time the user will have to wait.

Optimistic caching to reduce latency

So our preferred way of caching for real-time systems is optimistic caching. In optimistic caching, you assume any reply you’ve got memorized is “fresh enough”. You can answer that immediately, and later check whether it “needs some refreshing”. Similarly, when you’ve got no answer, you answer that, or some alternative answer you do have. And the tradeoffs start here - suddenly, your system can answer no answer, and the whole design has to change to accommodate for that… quirk.

But it’s that process of adaptation to non-answers that makes the system fly. So it’s a very useful mental exercise.

On top of that, that if you can make sure your active data set fit in RAM (and you can always make sure it does by throwing money at it, if you have it), you can completely hide the time it takes to compute a value with minimal non-answers ever propagating through the system (say only a few after a system-wide restart).

Optimistic caching would, terribly simplified, look like:

def get_user(user_id):

cached_user = user_cache.get(user_id)

if cached_user is None:

def load():

user_cache[user_id] = database.get(user_id)

Thread(target = load).start()

return cached_userWhich, of course, you’d also write pythonically like:

@cached(user_cache)

def get_user(user_id):

return database.get(user_id)Hint: you don’t have to write that decorator. We have published it already, and with an Open Source license. Just get chorde. It does this and more.

But of course, this version of get_user can return None! That’s the non-answer we mentioned earlier, and the code that calls this function has to handle it somehow.

There’s no magic trick there. You have to sit down with a lot of coffee and figure out what to do when there’s just no answer.

But let’s discuss the other problems, those that do have some formula that mostly works.

Cache intermediate results

You might have noticed the example above is about caching the result of a function, and not the reply to an HTTP request.

Caching the whole HTTP reply of course is easier to deploy (usually a plugin here or there, a CDN or two). It’s also quite efficient, since it reuses almost 100% of the work involved in generating a reply. But it also restricts your options quite considerably, and it might give you no measurable benefit due to poor keying (ie: badly selected cache keys).

Always consider the possibility of caching functions, not responses. Functions are far more ubiquitous in your code, you’ll have more caching opportunities, and you’ll have much higher cache hit ratios (since you’ll be able to define better keys).

Deciding the TTL

That’s not as tough as you might think.

In a real-time system, your TTL will be forced down your throat, you won’t have to decide it. If you think you have the freedom to decide, it’s because you haven’t yet pushed the limits hard enough.

In all time-constrained systems, the TTL will have to be set to what you can afford. It will balance the need for freshness with what’s viable, what your hardware can compute with which frequency. Say you have 1M users and each projection takes 10 seconds, if you have 1000 cores at your disposal, then you will have to set the TTL to about 2 hours 45 minutes (10K seconds) or slower. Because that’s what the hardware can handle, and there’s no flexibility in changing the hardware. And even if there was, it’s a budgeting decision we engineers don’t usually make anyway.

So don’t sweat over the TTL. When the time comes, you’ll know what to set it to. If you do make budgeting decisions, wear your business hat, and make the decision from a business point of view, not an engineering one. Does it make sense to invest X money on this? If the answer is yes, do it. If not, just set a TTL that saves you money.

Sure, things get trickier with a hundred different kinds of requests, when you have to juggle the TTLs of all to prioritize some above others. But usually any sensible setting will do, and the business itself will push hard for changes if they’re needed (and pay for the bills too, when needed).

If you need a guideline for your starting point, ask yourself: how fast does the value you’re trying to cache change? If projections, for instance, can’t change more than a small percent during a day, there’s little point in a refresh period much lower than a day.

Do, however, decouple your decision about a reasonable TTL (ie: how stale a reply can be), from the asynchronous refresh period (i.e,: every how often a reply needs updating). One will be guided by business rules, and the other by available resources, so it’s a good idea to keep them separate. In our experience, the best way to accomplish this is to rely heavily on asynchronous refresh.

Eviction policies

There are whole papers about these, but bear in mind that most of those papers tackle very different, specific problems. Like the CPU’s memory cache. For per-function caches, the simplest decision of an LRU is usually more than good enough.

Refrain from less-than-LRU policies though (like random eviction). Those are prone to exhibiting weird behavior that will kill your cache’s efficiency, and implementing an LRU isn’t hard enough to justify crippling your system like that.

A related problem is how to limit the amount of data in the cache. We don’t want to get into the various types of cache stores just yet, but an LRU in memory needs a limit, and sometimes measuring that limit in bytes (which would be optimal in most cases, since we know how many bytes we can have for caching) might not be as easy (or viable) as one would like.

Trying to estimate the “size in bytes” of a complex object graph can be quite a demanding task, and trying to do this in the cache can bring its performance down. So sometimes we have to be content with limiting the number of entries, but beware it’s not entirely wise to put rats and elephants in the same room. Split your caches by rough entry size and you’ll have an easier time consistently enforcing resource limits.

Everything can be cached

If you need to answer in 100ms as we do, you cannot afford the requirement that your answer is always fresh. At the very least you can do pessimistic caching with a very quick TTL.

Whenever possible, make sure you reserve a portion of that TTL to start computing a new value, so you can get the best of both worlds: always get some answer, almost always low latency. That something we call an asynchronous refresh.

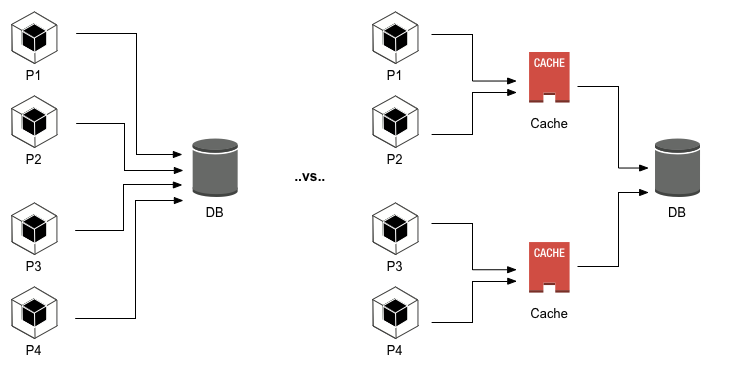

But, most importantly, a cache will shield your not-so-scalable resources, like relational databases, from the traffic surges that are inevitable. When this shielding becomes an integral part of an architecture’s design, the cache ceases to be a mere optimization and becomes a critical component. It’s seldom given the importance it has, but an inefficient cache can be as damaging as a dead load balancer. And “no cache”, is a good example of a very inefficient cache.

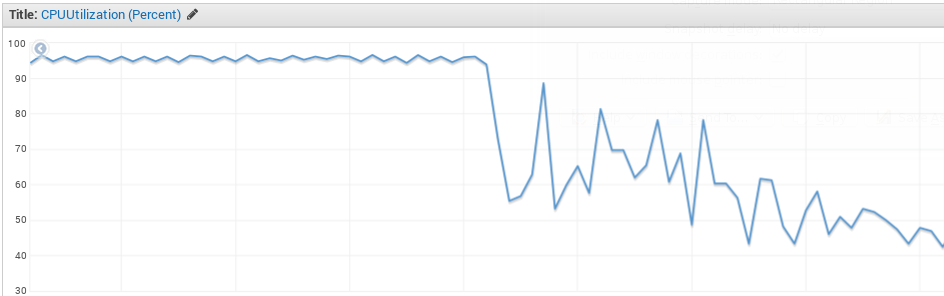

And this in fact happened to us just recently. A simple cache for a region (function group) became too small to hold the active data set, and the effect was disastrous. A simple fix (once we spotted the troubled region, which requires lots of log browsing and lots of instrumentation), and the improvement was equally impressive:

The rule of thumb is simple. Rotational disks have an average response time of 8ms, so database access is very expensive for a real-time system. Don’t access any databases directly - do everything through a cache, and you’ll avoid those 8ms per operation, that can really add up to a lot very fast (yes, we have SSDs, I know, but SSD-backed database can add considerable latency too, just try it).

Total latency

Say you’ve got the following:

@cached(user_cache, ttl = 600)

def get_user(user_id):

return database.get_user(user_id)

@cached(balance_cache, ttl = 600)

def get_current_balance(user_id):

return database.get_balance(get_user(user_id))

@cached(history_cache, ttl = 600)

def get_history(user_id):

return database.get_history(get_user(user_id))

@cached(projection_cache, ttl = 600)

def get_projection(user_id):

return smarts.project(

get_user(user_id),

get_current_balance(user_id),

get_history(user_id))How long does it take for a transaction to get noticed by the projection module? get_projection depends on get_user, get_current_balance and get_history, so its latency will be 10 minutes plus the maximum latency of its dependencies. And its dependencies have dependencies, so you have your hands full.

Make it a point to always think about this. Don’t let this added latency surprise you, it won’t be pleasant, nor easily detectable.

Key cardinality

Up until now, all examples used user_id as key, and that’s fine. We can assume not all users will be active, and we’ll be able to size the caches to fit all active users at once.

But don’t forget to be mindful of the force of the cartesian product:

@cached(history_cache, ttl = 600)

def get_transfers(user_id, destination_user_id):

return database.blah...That line there just made it impossible to hold everything in memory. If you happen to have a reasonable user base, with reasonably connected people, using this composite key didn’t just double the cardinality, it made it quadratic!. Ouch.

A cache over a key with high cardinality will provide very small benefits, and may not be worth your trouble.

Remember that adding caching to a problem gets you two problems - make sure you got a real measurable benefit from importing that extra problem. Multidimensional keys are going to be necessary, but as you make a point of thinking about total latency, also make a point of mentally sizing up the key space.

If your key space is big (or huge), we find it best not to invest many resources in caching that aspect of your computations, since it will be an uphill battle. It’s preferable to get the low hanging fruits and walk away while you’re ahead.

Executors

As the example of asynchronous refresh has shown, actual computation doesn’t happen on the main thread (if there is such a thing), and for a good reason. You don’t want to stall request processing while computing new values, because you already have a value you can work with, and latency matters.

There are several ways to schedule this asynchronous computation, and they all have slightly different tradeoffs:

-

Thread pools: quite simple to implement, they’re most likely your main workhorse when it comes to numerous small tasks (like get_user). They avoid having to serialize keys and responses, and having to communicate with external processes, so they’re fast. They also scale with your system, which is a very nice property. But they can be chaotic with big systems, since each process will require its own thread pool, and making them coordinate (we’ll talk about that some other time) will take a lot of effort.

-

Process pools: not much to say, they’re a slightly more scalable (but not by much) version of thread pools. You’ll need some form of IPC, but they stay within the same machine (or they’re called something else), so they’re more or less the same. They do require serialization of keys and values (ouch).

-

Task queues: this is for the big boys. When you have a complex enough system, you’ll feel the need to extract all this heavy-duty logic which is in your way, and be able to push tasks to a shared queue that knows how to distribute the tasks among many workers. Kinda like Celery. Making it interact properly with your main application will take more work than both of the above, but it will be easier to coordinate complex tasks.

What’s next?

So, we’re getting to a rather long winded post here, and as hinted in the previous section, it’s time to put off some subjects for our next post.