An in depth look into caching (Part 2)

Once upon a time…

…we posted about caching.

Time to post about caching again.

This time, we’re going to concentrate on the complexities of caching at scale. You know, you have a big honking piece of a datacenter crunching numbers so you can post the most awesome kitty pics. That’s what the internet is for after all. And you want your awesome kitty pics to appear in less than 100 milliseconds because… well, teenagers are impatient.

So we talked about how we want to cache everything, how to decide the TTL, more or less, and all those things that you can read on our previous post on the matter.

But we didn’t pause to ponder what would happen if we had 2000 cores in a few hundred servers all hitting the database to fetch that address for that insanely cute kitten.

We’ll do that now.

Things can go wrong

And things will go wrong.

When we work at those scales, several things can and will get out of hand. Just to name a few:

-

Memcache dies under the stress

Yes, we know, Memcache is fast. Or Redis, whatever you use. But at some point you realize that even the Titanic sinks. Or Memcache in this case. The problem: you’re hammering your Memcache instance with 2000x redundancy. Call that overkill?

-

Split-brain

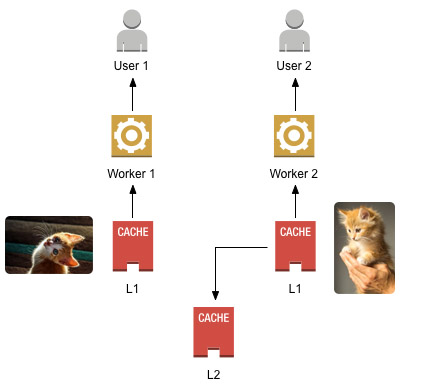

Some of the workers on the fleet think the above cat is the one, while others think it’s this one:

And all of a sudden millions of people are torn apart by an impossible choice. When you’ve got more than one source of truth, shit happens. We’ve all failed to learn this universal truth.

-

Concurrent redundant recomputations

Say you escape from the above, you may find yourself with another sinking boat - your database. Everything was fine until this huge entry expired and you’ve got 200 copies of the same query bringing your database to a halt. Servers need to cooperate to avoid this chaos.

-

The home page is slow

Wasn’t caching supposed to fix this? Well, yeahnotsomuch. Sometimes on-demand refresh isn’t fast enough. That’s especially the case for insanely popular items that may get queued behind a sea of irrelevant outliers.

-

The impossible tradeoff

You need more compute power, and add more cores. But since each core needs its quite huge L1 cache, you ran out of RAM again! Something’s hinky.

Ok, that’s a lot of ground to cover, so let’s start from the beginning and see what we can do with a few kilobytes of blog post.

Bottlenecks and single points of failure

If you’re lazy like all good programmers, you’ll probably start with a single lonesome dictionary (or LRU if you’re cunning) as your cache, but soon grow beyond the critical mass necessary to break the laziness barrier and get busy putting stuff into a Memcache.

And you may stay there for a long while, because if Memcache doesn’t rock, it’s only because it doesn’t know how to play the guitar just yet. So since it can take quite a pounding, you’ll realize quite late in life that you’re abusing it enough that it’s starting to cry out in pain. And if you’re lucky there’s going to be some monitoring in place to hear that tree fall.

Naive architectures tend to grind to a halt when put under significant loads, and since caching is usually an afterthought (though it shouldn’t be, we talked about this), it always tends to start naive.

At this stage of naivety, you may have one of the following very basic architectures:

-

Single-tier shared cache

All workers in your fleet communicate to a single, shared Memcache (or Memcache-like) service. The service might be a single Memcache instance or a cluster of Memcaches, but it works as a whole. And if it fails, your entire system goes down. Ouch.

-

Single-tier in-process cache

The proverbial dict. Or LRU. It’s a miracle it managed to scale like this, but sometimes it just works. For a while. It’s resilient, though. At least that can be said about this approach.

-

Two-tier in-process LRU + Memcache

We call the LRU the L1, and Memcache the L2. Savvy. Just, sometimes, not enough.

The problem with the single-tier architecture is, obviously, the huge, red, blinking, dressed-red-fluorescent-paint lit-with-black-light single point of failure. You don’t want something like this over your head. Or under your feet, supporting your entire infrastructure.

Because even if it were stable as a rock, there’s one failure mode that’s coming, as sure as winter: bandwidth bottleneck.

All traffic to your worker fleet will end up hitting your shared cache, since workers have no in-process memory. This means that while your worker fleet will scale to handle the load, the cache will not. And if you’ve got hot items, which in all likelihood you have (or caching wouldn’t be very useful), even the best consistent hashing scheme won’t avoid the overload of whichever shard gets to host this evil most frequently accessed item.

The two-tier architecture can handle this better, since it has an L1 that will absorb a portion of the bandwidth and make the whole network more efficient. But as your fleet grows, the efficiency of the L1 gets diluted, and the architecture quickly degenerates back into the behavior of the single-tier one.

We’re not even going to bother criticising the single-tier in-process one. No one could expect that a reasonably large fleet using that strategy wouldn’t DoS the database with redundant work, as each worker in the fleet computes the same thing over and over.

This is not to say that those strategies don’t have a niche place, in less critical parts of the system. But those parts don’t need their own blog posts now, do they?

Meet the cache stores

We keep mentioning tiers, but haven’t actually described what they are. Aside from the dictionary definition, caches can be understood in two levels.

On a low level, a cache may be a data structure or service that holds onto values ready to be retrieved at a moment’s notice. You’re already reading about caching so you probably have enough of an idea about this concept, we don’t need to go any deeper than that.

That, we call a cache store. Something that stores stuff. It may be a hash map, it may be an LRU, a service like Memcache, or even a database if it’s faster than the source of the data it’s storing - why not.

On a higher level, a cache may refer to an architecture - a way of knitting stores together to form a solution that solves a need for caching. Like, in our case, the kitten store: it uses many stores cooperating in some fashion, let’s say this naive two-tier LRU + Memcache way, to produce enough cuteness for today’s teens.

So a tier is the role a cache store fulfills in the whole architecture. Stores come in all forms and colors, but we use just a few that we found useful:

-

The LRU hash map

It combines a hash map (to access values by key) with a priority queue (by last access time) to be able to evict the least-recently-used item when space runs short. It’s a fast, low-latency, flexible in-process store that can serve many use cases, so it’s a workhorse of any real-time deployment.

-

Memcache

We know it, no need to waste e-ink describing it further. It does have a nasty drawback that it has several… uncomfortable limits. For one, values cannot be bigger than 1MB in size. Sometimes you need more. For another, as any remote caching service will require - any out-of-process one in fact - it requires serialization of both keys and values, and that’s CPU-intensive.

-

The filesystem

With an appropriate layout of course, it can store files. No surprise there. Within files, you can store data. So it works very well to cache lots of stuff, especially big objects that can be trivially mapped into files. We use it preferentially when the file can be readily used mmap’d. Yes, that’s two “m”s. Go read the link, it’s black magic. I’ll wait. The only sad thing is that it’s server-local: mmapping files over networked filesystems isn’t advisable.

-

S3

Kinda like the filesystem, but remote. It does preclude mmapping, sadly, but if you don’t need to mmap, it’s a good option. Filesystem over NFS works for that case too.

And while the following isn’t technically a cache store, since it’s static, it can be extremely useful to store snapshots of slow-evolving cache stores, so we’ll include:

-

Flat-buffer bundles

Serialized structures in such a way that you can use them as-is, directly from the file, like inverted indexes, or flat buffers (as in Google’s library). The key difference from a filesystem-based cache being that bundles store all key-value pairs in a single memory-mapped region, as opposed to storing one key-value pair per file.

We’ll certainly talk more about the various stores in a follow-up post. Lots of cool things to talk about here. But for now let’s concentrate on big architectural decisions.

Meet the tiered cache

All those stores can be combined to form a sort of composite cache store. The most common combination method is the inclusive tiered cache. Such caches are composed of N tiers, L1 to LN, and lookups test the tiers in increasing order until a fresh item is found in tier Li. When that happens, that item is “promoted” into lower tiers for further access.

This works well to combine the properties of cache stores. If S3 has unbounded size but cannot mmap files, but the filesystem can map them but takes long to do so, we can hold already-mapped files in an LRU, then we can make a tiered cache with:

-

L1 = in-process LRU

-

L2 = local filesystem

-

L3 = S3

L1 cannot hold many items (due to max open file limits), but that’s ok because when we have too many, we can close one to open another. The local filesystem isn’t unbound, we might not be able to fit all the files there, but S3 surely can - we’ll just have to download them (takes time), but the local filesystem tier shields our system from that latency.

So mature caching architectures start to take shape, in the form of multi-tier cache stores made out of complementing technologies. We also solve the bandwidth bottleneck, since the L2 can now absorb a lot of the bandwidth going to/from the L3, making the L3 scale better. It may even hold its own better during an L3 outage, since the L2 is big enough to hold lots of entries. Still not all, but it’s making good progress towards eliminating the SPF too.

And if you need an L4, don’t be shy. You might need one, say, if you have multiple datacenters.

Cool.

Concurrent redundant recomputations

This is a hard one. This is where having a library (coff chorde coff) abstracting away “good solutions” (which can certainly evolve in time) is a gold mine.

This along with the next (coherence) are probably two of the most difficult problems of adding a cache to a growing system, and it deserves respect.

That said, there are a couple of simple techniques that can have a huge impact on the performance of your cache. It doesn’t always need to be perfect. But if our hypothetical “kitty store” were to be extremely heavy on our resources, guaranteeing that we won’t do something twice becomes quite important.

And that’s what concurrency control is about. When a key in the cache is about to expire, if we have a big cluster of machines handling requests, all of them will want to refresh the value at the same time. It’s like the cache is failing us when we need it most: to avoid a huge stampede of requests reaching our precious, limited database.

There are many ways to counter this:

-

Use a task queue (like Celery)

..to sort out and de-duplicate tasks. A simple way to de-duplicate is to check the cache key for freshness before starting an expensive task, but some queues natively support task de-duplication (or write-coalescence), which would of course be a good thing.

-

Randomize refresh times

This is so simple it’s embarrasing, but it’s surprisingly effective. Spreading the load in time is a neat secondary effect. Just make each of your workers pick a different, random refresh rate. This will cause some workers to effectively become brokers without having to code any complicated logic. Sadly it gives no guarantees, but it’s very cheap to implement.

-

Coordinate

Explicitly, among workers. There are many ways. We’ll discuss some.

-

Mix and match

You can both coordinate and randomize. Useful if coordination itself becomes a bottleneck (and it will).

For coordination, a well known pattern, at least in the Python community, is the dogpile locking pattern (named after the library that made it popular), where keys are marked in the cache as “locked” when a worker is about to start a recomputation. This needs support from the cache store (whatever it may be) for some atomic locking operations, and is sensible to dead workers that abort a computation but fail to unlock a key. It has the benefit of simplicity, and of having multiple implementations out there to pick from.

A technique we prefer over the dogpile pattern, is that of promises. Whenever a worker starts a computation, it will first renew the entry in the cache, to notify everybody that it’s not in need of refreshing (in truth, to fool other workers and convince them not to refresh it just yet).

It has the benefit of being transparent to readers (they don’t need any logic), and extensive support of most caching stores (it can be implemented with very few primitives). Promises themselves can be renewed while the worker is still alive and happily computing, but made to automatically expire if it suddenly stops, so this also is more robust for very long and expensive computations that we wouldn’t want to risk doing twice, yet are also not willing to wait for long timeouts if (or when) a worker dies.

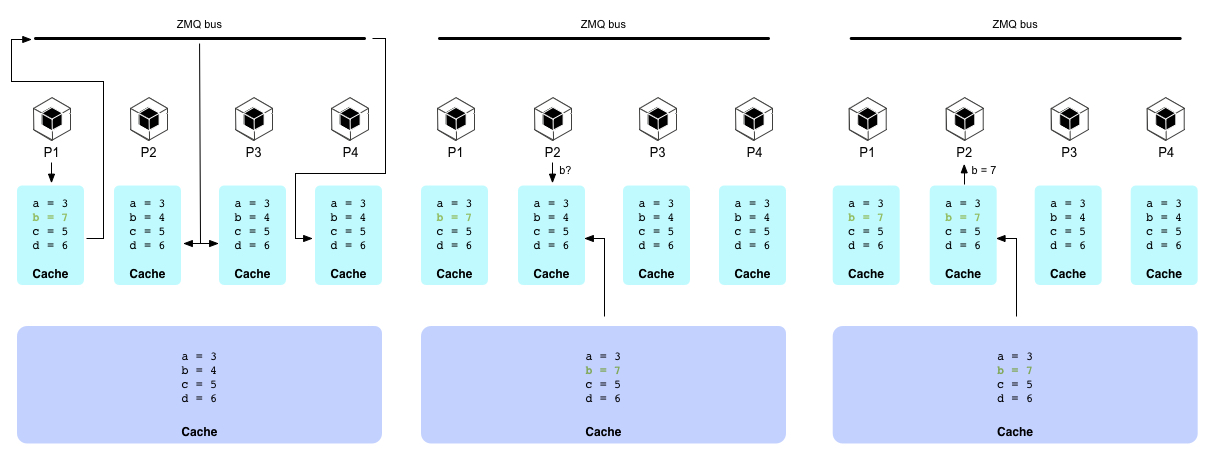

And, finally, for those rare occasions when we really need perfect coordination, actual coordination through a shared gossip bus. There are many ways to implement said gossip, but if you want some inspiration, we kinda love zeromq for those things. Redis pub/sub also works well.

Keeping the gossip bus ticking while workers come and go, fail, get stuck, explode or simply vanish, is no small feat. In fact chorde is still evolving in that regard, and that’s probably the biggest benefit of using a library, where the experience and fixes of many users can be pooled. You can also opt for Zookeeper, if you favour heavyweight solutions, but you surely want to draw on other projects’ experiences.

Coherence - or what the split brain hasn’t got

When you’ve got multiple tiers that work independently from each other, sooner or later you’ll suffer from split brain. Whoever writes to the cache, or whoever hasn’t yet promoted the fresh entry into its L1, will see stale, or worse, fresh data that doesn’t match what others have. If your requests are routed round-robin, or in a way that doesn’t guarantee users will hit the same worker every time, then some times they’ll see one value, and some times they’ll see another, confusing the hell out of them. Maybe even starting wars! (hey, kittens are serious business)

The problem is, lower tiers need to hear when an upper tier updates a key they’re holding onto. Checking every time would work, but defeat the purpose of having fast, low-latency cache stores as lower tiers. So it would be best if, somehow, the upper tiers could simply “notify” lower tiers when they change something.

And this is what coherence gossip is all about. If you have a suitable pub/sub channel, every worker can publish task-started, finished and aborted messages, and respond to general queries about tasks in progress (for new workers that haven’t been paying attention to previous chatter), and you can solve both concurrency and coherence issues like this.

With suitable filtering of channel subscriptions, you can even avoid having gossip traffic grow as O(N2) (which would really suck).

Our current implementation tries to be fully distributed, and does, roughly, the following:

-

Use a consensus protocol (any) to define a “broker” (a worker that will handle general queries). Brokers could be sharded (keys are split in partitions and each partition gets its own broker) if they get overloaded, but we haven’t reached this point yet - they can handle a lot of load - and the consensus protocol will pick a new broker if one dies (detected by listening for heartbeats).

-

Split all keys into partitions, and subscribe to the partitions that are present in your L1. If your L1 is huge and your pub/sub can’t handle thousands of subscriptions efficiently, you can make the partition key lower-cardinality to keep it manageable.

-

Before computing a new key:

-

Issue a work-in-progress query to the broker. If it doesn’t respond in a heartbeat, run the consensus protocol to become a broker.

-

The broker responds by checking its memorized list of in-progress tasks. If nobody is processing the key, mark the caller as in-progress and tell it to start crunching numbers.

-

If there’s an old entry saying a worker is working, request confirmation by publishing a request for updates on the pub/sub. Anyone with WIP entries not replying in a heartbeat will be marked as aborted, and if the requested key is one of them, give the caller the honor of computing that key.

-

-

When finishing updating a key on the higher tier, publish the task’s completion on the pub/sub.

-

When receiving a task completion notice, if the key is in the local tiers, expire it.

-

When joining the fleet as a broker, issue a general request for WIP entries to start serving.

It’s a complex protocol, with lots of nuances, but it keeps all tiers consistent, and that’s worth the effort. Notice that the gossip involves only keys, never values. It makes little sense marshalling values early among workers, since they may never need them. It’s best to simply remove the inconsistent entries from the lower tiers, and let the upper tiers serve them when needed.

The MFU set

With all this, the home page may still be slow, a WTF moment nobody enjoys.

It so happens, that with all the magic going on, sometimes DoSsing some cache shard is unavoidable when The Most Frequently Used key expires. You’ll have tousands of workers querying the gossip bus, you’ll have thousands of workers fetching from the L3 or L4, and network congestion may even make the coherence protocol misbehave and get you a few dozen identical queries on that overworked database because some broker missed its heartbeat deadline or some such.

So it’s a good idea here to remember that users are predictable. Especially when you’ve got a cache, that can tell you the most popular items simply by inspecting the LRU’s priority queue.

So it’s a good idea to have some background task regularly walking the MFU set and proactively refreshing them in the cache, just to avoid the nightmare above.

Maybe you don’t even need to query the LRU to get the MFU - sometimes it’s as predictable as “the home page”. You know, the page everybody has to look at before they start using your service. Which is kind of predictable.

So long (has this post been)

And thanks for all the fish. Lets better leave some for later.

In the next post, we’ll take a deep dive into the various data structures one can use as cache stores, and some tools to tackle the last problem we mentioned before, that impossible tradeoff.

We may even have some code, which was MIA in this one. Sorry for that.

See you next time.